We need better thinking on US pharma patent reforms

With the crucial Iowa Democratic caucus set to take place on Monday, it is looking increasingly likely that this year’s presidential election will be pivotal for the future of pharmaceuticals patents in the US.

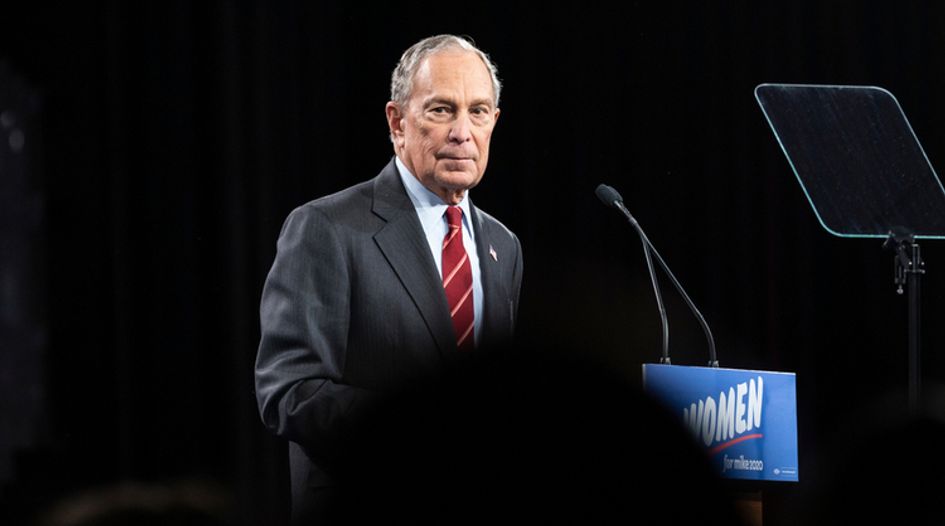

This week, centrist Democratic candidate (and former Republican) Mike Bloomberg announced a commitment to restricting innovators to only one patent relating to any particular drug. This follows equally radical pledges by party frontrunners, such as Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, to weaken the IP protection available for life sciences inventions. And, with the country’s unusually high drug prices likely to be a key issue with voters in the presidential election itself, it would not be surprising if President Trump toughens his stance too.

What should worry IP professionals on both sides of the innovator v generic/biosimilar divide is the increasingly simplistic, headline-grabbing nature of the discussion around US drug patents. It is a debate that makes it less likely that future IP reforms will ensure that innovation is properly incentivised while addressing legitimate concerns about competition.

Bloomberg unveiled a broader range of proposals to lower drug prices on Monday, 27th January. Regarding IP, he proposes to “bring generic drugs to the market faster by limiting brand-name drug makers to one patent that lasts 20 years”, as well as by instructing the National Institutes of Health to enforce and seek royalties from state-owned IP rights.

The first of these policies would constitute a major departure from the existing US patent system, in which life sciences companies – like innovators in all other industries – are free to seek rights for numerous distinct inventions, regardless of whether they relate to a single product. Though the proposals are not spelled out in more detail, they would presumably entail excluding from patent protection many innovations, such as methods of manufacture, new formulations and new medical uses of an existing drug. The policy also implies an end to patent term extension.

This is not the kind of policy one might have expected from the former Republican Mayor of New York, who is otherwise positioning himself as a centrist in the race for the Democratic candidacy. But the move follows years of growing criticism of pharma patents and patent-owner tactics, which have been blamed for causing the country’s unusually high drug prices by keeping generic/biosimilar competitors off the market for excessive periods of time. The acquisition of large numbers of patents by pharma companies to protect their leading biologic drug franchises – most notably AbbVie’s Humira – has caused particular outrage.

Several frontrunners in the race for the Democratic nomination have also staked out radical positions on drug patents. Elizabeth Warren has stated that in her first 100 days as President she would use executive powers to tackle pharma companies “that abuse our patent system”, by, for example, deploying compulsory licensing powers to “bypass patents” for drugs such as Humira, Truvada, Naloxone and Harvoni.

Senator Bernie Sanders has also tabled legislation to establish a government bureau to issue compulsory licences on patents and other exclusivities when drugs are deemed to be too expensive. Such policies represent a fundamental shift from the idea of a patent as a dependable right towards the concept of IP rights as highly-contingent exclusivities.

In fact, Joe Biden is the only leading Democratic candidate who has not made a comparable proposal, meaning that there is a good chance the eventual Democratic nominee will be committed to a major shift in pharma patent policy. With drug costs such a hot topic and a tight election to win, Donald Trump – who is no stranger to populist rhetoric and measures – would no doubt feel an obligation to come up with a plan of his own.

This situation will be a concern to drug innovators, whose significant investments are underpinned by strong patent rights (including for new therapeutic uses and new formulations, among others). And it is alarming that the ascendant narrative seems to take little account of the essential role played by IP rights in promoting medical innovations or of the complexities of the patent system.

The extent to which the nature of the US patent system contributes to the country having higher drug prices than other developed countries is debatable. The most salient differences between the US and European prescription drug systems relate to how treatments are marketed, purchased and paid-for, not to their patent regimes.

But to the degree that patent system reforms have a role to play in reducing prices, politicians would do better to ask what IP barriers stand in the way of generic and biosimilar competition in the US that are absent in other countries (US politicians and media constantly compare drug prices with Europe, but never compare IP systems).

European countries do not frequently issue compulsory licences and – though patent thickets there tend not to be as large – do not limit the number of patents that can relate to a drug franchise. The differences between IP systems on either side of the Atlantic that I have heard emphasised by corporate patent counsel at international biosimilars companies are more subtle:

- Stricter rules on double-patenting and added subject matter at the EPO make it harder than in the US for innovative drug companies to make strategic use of the application process.

- Inter partes review proceedings at the USPTO are vastly more expensive (especially once legal fees are factored in) than opposition proceedings at the EPO, making it impractical to make administrative challenges to large numbers of US patents relating to an innovative drug. US estoppel rules add to the risk of using administrative proceedings against drug patents.

- The requirement for drug imitators to file at the FDA before they have standing to challenge drug patents in court also makes it harder to break through patent thickets and concentrates commercial risk at the end of an expensive biosimilar development process.

However, politicians are not about to gravitate towards the technical discussions needed around potential patent reforms; these are complex and less likely to grab headlines or boost candidates’ popularity. So maybe it is time for life sciences IP professionals to force themselves into the debate: not to make crude pro- or anti-patent statements, but to help the public understand the important nuances of the issue at hand.